Carnatic Music#

Melodic Concepts and Performance Structure#

Carnatic Music in Performance: Instrumentation#

Vocal-led performance group#

Fig. 2 A Carnatic music performance, led by the vocalists R.K. Shriramkumar, Amritha Murali, Ramakrishnan Murthy, accompanied by Madan Mohan on violin, Arunprakash Krishnan on mṛdaṅgam and Nanditha Kannan on the tambūrā. Image by Rajappane Raju.#

The most popular performance format today is vocal-led, either by a single or multiple vocalists.

The vocalist is typically accompanied by a violinist. In compositions, the violinist plays in unison with the vocalist, or at the octave, leading to a largely monophonic melodic texture between the two. At other times, in the more improvisational sections (known as manodharma saṅgīta), the violinist shadows the vocalist, leading to a more heterophonic melodic texture.

The percussion section is led by the mṛdaṅgam (double-ended drum), and other percussion instruments may include the ghaṭam (clay pot), kañjīra (small frame drum), and morsing (mouth harp).

An important feature is the tambūrā drone played throughout. This can be performed using either the physical instrument, the tambūrā, or an electronic imitation of the instrument, known as a śruti box.

Implications for MIR: Notwithstanding the dominant monophonic melodic line, the overall instrumental texture is heterophonic, which is a challenge for predominant pitch extraction.

Instrumental-led performances#

There are also instrumental-led performances, without vocalists: for example, groups led by vīṇa, veṇu (flute), violin, saxophone, mandolin, and others.

Fig. 3 Vīṇa performance led R.S. Jayalakshmi and Charulatha Chandrasekar, Umayalpuram Mali on the mṛdaṅgam, and Alathur Rajaganesh on the kañjīra. Image by Rajappane Raju.#

In addition, there is the closely related tradition, Periya Mēḷam, performed more often in temple and ritual settings but also having a concert tradition. Here the main instruments are nāgasvaram, tavil and tāḷam cymbals.

Fig. 4 Periya Mēḷam performance - nāgasvaram by Iyermalai A B Selvam and Thiruloki T J Venkateshwaran, tavil by Adyar Silambarasan and Ennairam S Kamaraj. Image by Rajappane Raju.#

Implications for MIR: Presently, in MIR on South Indian art music there is a greater focus on Carnatic vocal performance. However, instrumental-led performances are an important element of the style and there is scope for more exploration of these.

Musical Formats and Performance Structure#

Pre-composed or improvisational?#

In Carnatic music there are formats that are more precomposed, and formats that are more improvisational in their respective creative processes. Typically, the strongly precomposed formats are referred to as ‘kalpita saṅgīta’ or ‘compositions’, and the more improvisational sections are referred to as ‘manodharma saṅgīta’. It should be noted that in practice the performance of compositions often also includes some spontaneous variations (some extemporization), while the manodharma sections are based around well known, and hence precomposed, phrases [Ram07]. Therefore, the performance of both formats actually include improvisational and precomposed elements, but to different degrees and in different ways [NW06, Pea21]. Furthermore, a composition itself is a composer’s imagined creation, that originally involved both improvisational and precomposed elements, and that later becomes part of the repertoire of precomposed formats.

Variation in the performance of a given composition#

In this tradition, compositions are handed down orally through the teaching lineage, and as a result, different lineages may perform slightly different versions of the same composition [Pea22]. Therefore, published notations may also differ despite being of the same composition. Furthermore, as noted above, experienced musicians may add melodic variations on some lines of the composition during performance [Vij09]. The upshot of all this is that we cannot expect a published notation to align precisely with what is performed.

Implications for MIR: The fact that published notations will not precisely concur with what is performed, and that much of the performance is improvisational with no published notation, means that many that research questions addressing this style can only be approached by analyzing audio recordings. As a result, Carnatic-based MIR tends to focus on audio.

Kalpita saṅgīta#

Types of compositions include kīrtana, varṇam, padam, and tillānā. These usually have three sections - pallavi, anupallavi and caraṇa. The pallavi is the refrain-like portion that returns again after the anupallavi and caraṇa. The presentation of a composition is in the order ‘pallavi-anupallavi-pallavi-caraṇa-pallavi’ (see Fig. 5).

Factors that characterize the different compositional formats include structural details, melodic and rhythmic aspects, and also the lyrics. For example, in its structure a kīrtana usually has a pallavi, anupallavi and carṇa, the melody of the pallavi is typically in the middle register, the anupallavi extending to upper registers and the caraṇa usually combining both registers, the kīrtana has lyrics (sāhitya), and the style is melismatic.

Fig. 5 Graphic showing the typical structure of a composition, e.g., a kīrtana. Time runs from left to right, with the pallavi opening the sequence.#

Manodharma saṅgīta#

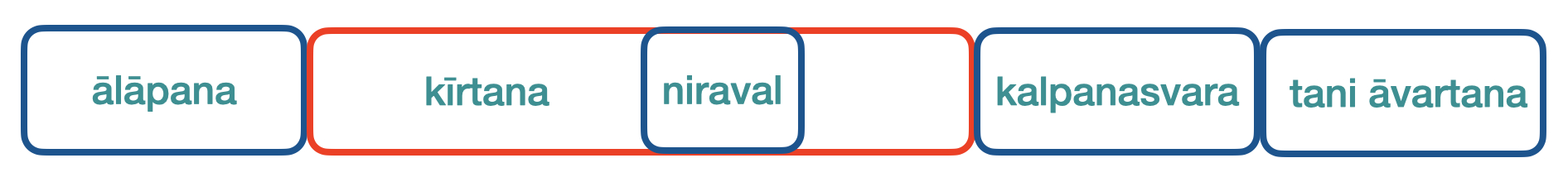

Manodharma formats include ālāpana, niraval, kalpanasvara, and tani āvarttanam.

Manodharma saṅgīta can be translated as ‘music of the imagination’ [Kas00] referring to the way in which these formats are created on the spot (not fully pre-composed), based on existing materials (phrases) and using structural principles that are acquired by musicians through practice and exposure to the style.

These formats are typically performed alongside a composition, usually in the same rāga. For example, if the composition is a kīrtana in rāga Bhairavi, then the performer would usually open with ālāpana in the same rāga. Ālāpana is a creative exploration of the rāga, without lyrics or meter, which is sung using extended vowels and syllables such as ‘ta’, ‘da’, ‘ri’ and ‘na’. Next the vocalist would perform the kīrtana, including a section of niraval (extemporization on a particular line of sāhitya in the kīrtana, chosen by the performer) and then end with some rounds of kalpanasvara (improvised passages of sargam syllables in different speeds). The tani āvartana is the percussion solo, involving a combination of pre-composed (by the percussionists involved) and improvisational elements.

Fig. 6 Graphic showing how manodharma elements can be integrated together with a composition (in this case a kīrtana) in a performance. Time runs from left to right, with the ālāpana opening the sequence.#

Implications for MIR: The performance of one item can vary in length from just a few minutes if only a short kīrtana is performed, to over an hour if all of the manodharma elements are included. The relatively long duration of a single item, containing multiple sections with differing instrumental textures and rhythmic structures can be challenging for some MIR processes.

Carnatic Melodic Concepts#

Rāga and rāga bhāva#

The melodic frameworks on which Carnatic music is based are known as rāgas. One of the main aesthetic goals of Carnatic performance is the correct expression of rāga. Rāgas can be understood as collections of phrases or melodies, comprising gamakas (ornamentation) and svaras (notes) that are considered part of the melodic framework, and performed in ways that follow the grammar of the rāga.

Each rāga has its own character or mood, referred to as rāga bhāva. Rāga bhāva cannot be adequately described using words such as simple emotion terms, but it can be experienced when listening to or performing a rāga.

Svara#

Svaras are note-length units with theoretical pitch positions, and are referred to using sargam syllables – sa ri ga ma pa dha and ni. Sargam syllables are used in written notation, and also in certain musical formats when the svara names are sung.

In practice, most svaras are performed with gamakas (ornamentation), rather than as plain notes [Ram04]. Therefore, although svaras are often referred to using the English term ‘notes’, they differ from notes in that the gamakas with which they are performed are considered integral to the svara [Vis77].

Gamaka#

Many rāgas involve heavy use of gamakas (ornamentation) such as oscillations, slides and flicks to other pitches. Although gamaka typologies can be found in musical treatises, in practice, gamakas tend to evade categorisation due to the many subtle variations found in performance [Vis77]. Nevertheless, such typologies can provide some idea of the range of gamakas performed, as can be seen in this webpage based on a gamaka typology from the Saṅgīta-sampradāya-pradarśini [Dik08], which draws on original work by Gopala Krishna Koduri.

It’s important to note that gamakas are not superficial decoration but rather are integral to musical meaning [Vis77]. For example, when two rāgas have the same svaras, it is often the gamakas used that disambiguate the rāgas [Kas00].

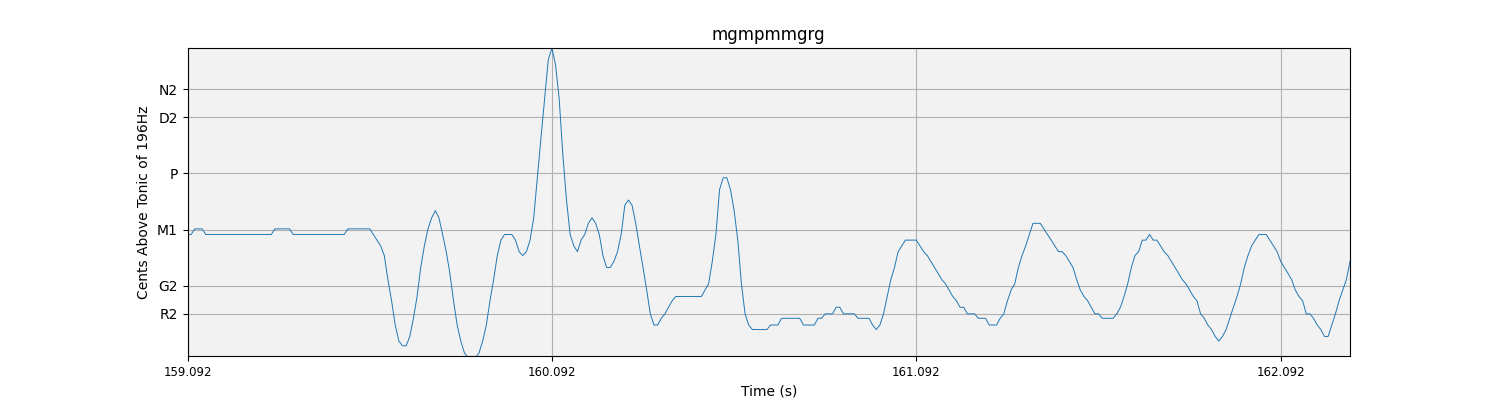

Gamakas, can greatly alter the sound of the notated svaras (notes); for example, some gamakas do not rest at all on the theoretical pitch of the notated svara, and instead involve oscillations between pitches either side of it [KI12], as seen in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 Pitch movement for the sañcāra ‘mgmpmmgrg’ from the recording of Koti Janmani in rāga rītigauḷa, performed by the Akkarai Sisters. It can be seen that the long ga at the end of the phrase is performed as an oscillation between ri and ma, which is typical for this rāga.#

This oscillatory movement is particularly characteristic of the Carnatic style, and can often subsume individual svaras [Pea16]. The surface effect on the melodic line is that it typically has fewer stable pitch regions than many other styles, as seen in Fig. 7. Such qualities makes it impossible for researchers who are not themselves Carnatic musicians to reliably identify svaras from audio recordings. Recent work has attempted to automate this task by creating descriptive transcriptions that assign svara names to key points in the melodic flow [RPS17, RSPS19, VPMA20]. However, such descriptive transcriptions do not necessarily align with the underlying svaras that musicians would use to notate the phrase, which may or may not be a problem, depending on the research question and purpose of the transcription.

Implications for MIR: The heavy use of gamakas, especially oscillations, makes automated transcription of Carnatic music a challenging task.

Sañcāra#

Another important feature of the style is the structural and expressive significance of motifs and phrases known as sañcāras, which can be defined as coherent segments of melodic movement that follow the grammar of the rāga [Pes09, Vis77]. The term sañcāra comes from the Sanskrit root सञ्चर्, meaning to move. Although occasionally the term might be used to refer to phrases that are particularly characteristic of a rāga, the more common use of the term is in reference to any melodic segment that is coherent from a Carnatic music perspective.

These melodic patterns are the means through which the character of the rāga is expressed and they form the basis of various improvisatory and compositional formats in the style [IDBM13, Vis77]. There are no definitive lists of all possible sañcāras in each rāga, rather the body of existing compositions and the living oral tradition of rāga performance act as repositories for that knowledge.

Implications for MIR: Sañcāras are the building blocks of Carnatic music, and so there is considerable musicological interest in searching for them. However, as is the case with the related concept of ‘musical phrase’, there may be ambiguity regarding the borders of the sañcāra: for example, different annotators may segment at different hierarchical levels (for a related discussion in the context of Western popular music, see [BMK09]).

Characteristic phrases or piḍis#

These are phrases that can only be found in one rāga, and thus point clearly to that rāga. As explained by the Carnatic musician and musicologist, T. Viswanathan, “Each rāga has its own characteristic phrases which appear regularly in compositions, and which are guaranteed to produce instant recognition (and, if well performed, appreciation) in the audience” ([Vis77], p. 38).

Implications for MIR: Many rāgas will be identifiable from key characteristic motifs (piḍis).

Tambūrā drone#

The tambūrā creates a plucked drone, which includes sa (ṣaḍja) and usually pa (pañcama), the perfect fifth above (although in some rāgas, ma might be used as the other tone). Sa is set to the pitch in which the singer/instrumentalist feels most comfortable performing.

The ṣaḍja (sa) has a ‘tonic-like’ effect, where we feel a sense of rest on that tone, and hence it is sometimes referred to by musicologists as the ‘tonic’, even though no such term exists in Carnatic music.

Implications for MIR: sa can be placed at any pitch, and usually remains the same throughout a performance. However a few rāgas may be presented in the madhyama śruti, which shifts the position of sa. The fact that sa may be placed at any pitch means that for many MIR processes, pitch needs to be normalized to wherever sa is placed.

Note

The above sections (instrumentation, format, and melodic concepts) are authored by Lara Pearson and Brindha Manickavasakan (2022).

Rhythm and Percussion in Carnatic Music#

The rhythmic framework is based on cyclic metrical structures called the tāl in Hindustani music and tāḷa in Carnatic music. Both words originate from Sanskrit and have the same literal meaning of a “hand-clap”. For consistency and convenience, when it is clear from the context, we will use the word tāḷa to mean both tāl and tāḷa when we refer collectively to the two traditions, and use the respective terms when referring to each music culture individually.

The rāga and tāḷa are the most important metadata associated with a composition and hence a recording of the composition. Each composition is composed in one or more rāgas and tāḷas.

Meter#

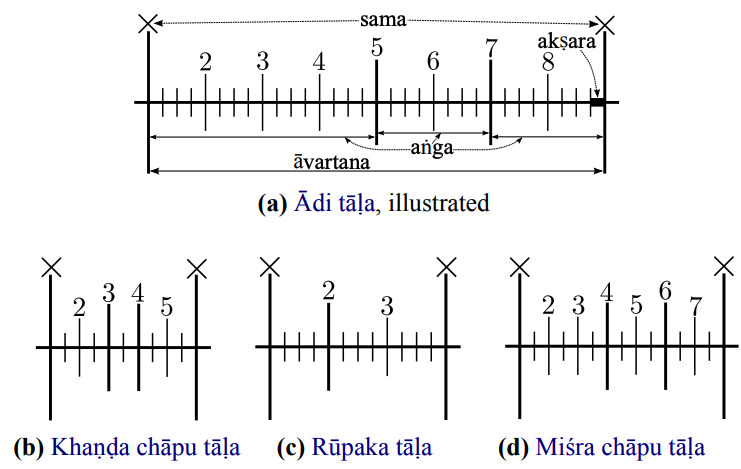

[Sam98] provides a detailed description of tāḷas in Carnatic music. In Carnatic music, the tāḷa provides a broad structure for repetition of music phrases, motifs and improvisations. It consists of fixed length time cycles called āvartana which can be referred to as the tāḷa cycle. In an āvartana of a tāḷa, phrase refrains, melodic and rhythmic changes usually occur at the beginning of the cycle. An āvartana is divided into basic equidistant time units called akṣaras. The first akṣara pulse of each āvartana is called the sama, which marks the beginning of the cycle (or the end of the previous cycle, due to the cyclic nature of the tāḷa). The sama is often accented, with notable melodic and percussive events. Each tāḷa also has a distinct, possibly non-regular division of the cycle period into sections called the aṅga. The aṅgas serve to indicate the current position in the āvartana and aid the musician to keep track of the movement through the tāḷa cycle. A movement through a tāḷa cycle is explicitly shown by the musician using hand gestures, based on the aṅgas of the tāḷa.

The common definition of an isochronous (equally spaced in time) beat pulsation, as the time instances where a human listener is likely to tap his/her foot to the music, is likely to cause problems in Carnatic music. Due the explicit hand gestures, listeners familiar to Carnatic music tend to tap to a non-isochronous sequence of beats in certain tāḷas. Hence we use an adapted definition of a beat for the purpose of a common ground, defined as a uniform pulsation. It is to be noted however that an equidistant beat pulsation can later help in obtaining the musically relevant possibly irregular beat sequence that is a subset of the equidistant beat pulses. The akṣaras in an āvartana are grouped into equal length units, which we will refer to as the beats of the tāḷa. The perceptually relevant hand/foot tapping time “beats” are a subset of this uniform beat pulsation.

The subdivision grouping structure of the akṣaras within a beat is called the naḍe (also spelled naḍai) or gati. The most common naḍe is caturaśra, in which a beat is divided into 4 akṣaras (in duples, equivalently 2 akṣaras). Another important aspect of rhythm in Carnatic music is the eḍupu, the “phase” or offset of the lead melody, relative to the sama of the tāḷa. With a non-zero eḍupu, the composition does not start on the sama, but before (atīta) or after (anāgata) the beginning of the tāḷa cycle. This offset is predominantly for the convenience of the musician for a better exposition of the tāḷa in certain compositions. However, eḍupu is also used for ornamentation in many cases. Though there are significant differences in terms of scale and length, as an analogy, the concepts of akṣara, the beat, and the āvartana of Carnatic music bear analogy to the subdivision, beat and the bar metrical levels of Eurogenetic music. Further, aṅga are the possibly unequal length sections of the tāḷa, formed by grouping of beats.

Tāḷa |

# Beats |

Naḍe |

# Akṣara |

|---|---|---|---|

Ādi |

8 |

4 |

32 |

Rūpaka |

3 |

4 |

12 |

Miśra Chāpu |

7 |

2 |

14 |

Khaṇḍa Chāpu |

5 |

2 |

10 |

Fig. 8 An āvartana of four popular Carnatic tāḷas, showing the akṣaras (all time ticks), beats (numbered time ticks), aṅgas (long and bold time ticks) and the sama (×). Ādi tāḷa is also illustrated using the terminology used in the dissertation.#

Carnatic music has a sophisticated tāḷa system that incorporates the concepts described above. There are seven basic tāḷas defined with different aṅgas, each with five variants leading to the popular 35 tāḷa system (Sambamoorthy, 1998). Each of these 35 tāḷas can be set in five different naḍe, leading to 175 different combinations. However, most of these tāḷas are extremely rare in performances with just over a ten tāḷas that can be regularly seen in concerts. A majority of pieces are composed in four popular tāḷas - ādi, rūpaka, miśra chāpu, and khaṇḍa chāpu. The structure of those four popular tāḷas in Carnatic music are described in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 8, all in caturaśra naḍe (division of a beat into two or four akṣaras). The different concepts related to the tāḷas of Carnatic music are also illustrated in Fig. 8. The figure shows the akṣaras with time-ticks, beats of the cycle with numbered longer time-ticks, and the sama in the cycle using ×. The aṅga boundaries are highlighted using bold and long time-ticks e.g. ādi tāḷa has 8 beats in a cycle, with 4 akṣaras in each beat leading to 32 akṣaras in a cycle, while rūpaka tāḷa has 12 akṣaras in a cycle, with 4 akṣaras in each of its 3 beats.

The case of non-isochronous beat tāḷas, miśra chāpu and khaṇḍa chāpu, need a special mention here. Fig. 8 shows miśra chāpu to consist 14 akṣaras in a cycle. The 14 akṣaras have a definite unequal grouping structure of 6+4+4 (or 6+8 in some cases) and the boundaries of these groups are shown with visual gestures, and hence form the beats of this tāḷa [Sam98]. However, in common practice, miśra chāpu can also be divided into seven equal beats. In this dissertation, we consider miśra chāpu to consist of seven uniform beats as numbered in Fig. 8, with beats ×, 4 and 6 being visually displayed. Similarly, khaṇḍa chāpu has 10 akṣaras in a cycle grouped into two groups as 4+6.

Percussion in Performance#

Most performances of Carnatic music are accompanied by the percussion instrument mridangam (mr̥daṅgaṁ), a double-sided barrel drum. There could however be other percussion accompaniments such as ghaṭam (the clay pot), khañjira (the Indian tambourine), tavil (a two sided drum) and mōrsiṅg (the Indian jaw harp), which follow the mridangam closely. All these instruments (except the khañjira) are pitched percussion instruments and are tuned to the tonic of the lead voice. Since the progression through the tāḷa cycles is explicitly shown through hand gestures, the mridangam is provided with substantial freedom of rhythmic improvisation during the performance. The tāḷa only provides a metrical construct, within which several different rhythmic patterns can be played and improvised.

The solo performed with the percussion accompaniments, called a tani-āvartana, demonstrates the wide variety of rhythms that can be played in a particular tāḷa. The solo performance by the percussion ensemble follows the main piece of the concert. The solo is an elaborate rhythmic improvisation within the framework of the tāḷa, but with much improvisation on the percussion patterns. The tani strives to present a showcase of the tāḷa with a variety of percussion and rhythmic patterns that can be played in the tala. The percussion instruments duel and complement each other in a solo of each instrument, with all instruments coming together to a cadential end. The patterns played can last longer than one āvartana, but stay within the framework of the tāḷa. A tani-āvartana is a showcase of the skill and talent of the percussion artists. It is replete with a variety of percussion patterns and hence is very useful for analysis of percussion patterns. The tani is often performed with a subset of the percussion instruments. The mridangam is always present, while the other instruments are optional.

Solkaṭṭu#

Percussion in Carnatic music is organized and transmitted orally with the use of onomatopoeic oral mnemonic syllables (called solkaṭṭu) representative of the different strokes of the mridangam. An oral recitation of these syllables is itself an art form called konnakōl, and is often a part of a tani-āvartana. The syllables used belong to mridangam, but is widely used with other percussion instruments used in Carnatic music. These syllables vary across schools, but provide a good representation system to define, describe and discover percussion patterns.

We consulted a senior professional Carnatic percussionist for the complete set of strokes that can be played with the mridangam. The stroke syllables of the mridangam represent the combined timbre of the left and right drum heads, and hence over 45 different strokes can be played on the mridangam. However, many of the timbrally similar strokes can be grouped together into syllable groups, assuming that such a timbral grouping is sufficient for discovery of timbrally similar percussion patterns. This timbre based grouping further enables us to work with the variability in syllables across different schools. The syllable groups, the symbol we use for them in this dissertation, and a short description is shown in Table 2. The different stroke names are not indicated in the table since they vary. For simplicity and brevity, we will refer to the syllable groups as just syllables in this work when there is no ambiguity. Finally however, we carefully note that the syllables also have a loosely defined functional role, and such a timbre based grouping used in this document is an approximation done only for computational analysis approaches.

Syllable |

Description |

|---|---|

AC |

A semi ringing stroke on the right head |

ACT |

AC with TH/TM |

CH |

A ringing stroke on the right head |

CHT |

CH with TH/TM |

DM |

A strong ringing stroke on the right head |

DH3 |

A closed stroke on the right head (variant-1) |

DH3T |

DH3 with TH |

DH3M |

DH3 with TM |

DH4 |

A closed stroke on the right head (variant-2) |

DH4T |

DH3 with TH/TM |

DN |

A pitched resonant stroke on the right head |

DNT |

DN with TH/TM |

LF |

Long finger stroke on the right head |

LFT |

LF with TH/TM |

NM |

A sharp pitched stroke on the right head |

NMT |

NM with TH/TM |

TH |

A closed bass stroke on the left head |

TA |

A closed sharp stroke on the right head |

TAT |

TA with TH/TM |

TM |

An open bass stroke on the left head |

TG |

Pitch modulated bass stroke on the left head |

Note

The section above has been adapted, with consent, from the PhD thesis of Ajay Srinivasamurthy [S+17]