Hindustani music#

The repertoire#

Fig. 9 Example concert setup for vocal concert in Hindustani music.#

A typical khayal performance can be led by either a single or multiple vocalists (Fig. 9) The vocalist is typically accompanied by a harmonium and/or sarangi. During the refrain of the compositions, the accompanist plays in unison with the vocalist, leading to a largely monophonic melodic texture. At other times, in the more improvisational sections (known as barhat), the accompanist shadows the vocalist, leading to a more heterophonic melodic texture. The percussion section is led by the tabla (bass and treble drums) for the khayal repertoire and pakhawaj for the dhrupad repertoire. A highly important feature is the tanpura drone played throughout. This can be played by either the physical instrument, or an electronic imitation of the instrument, of the likes of iTanpura iOS app or a shruti box.

Fig. 10 Example concert setup for instrumental concert in Hindustani music.#

There are also instrumental-led performances, without vocalists: for example, groups led by sitar, sarod, flute, violin, santoor, sarangi, shehnai, and others (see Fig. 10) In addition, tabla solo concerts are popular where the percussion takes the center stage, and the melodic accompaniment of the chorus is provided by harmonium or sarangi (see Fig. 11). Sometimes, artists take vocal accompaniment as well, to showcase the accompaniment style with vocal music which is evidently different from instrumental music in a solo performance scenario.

Fig. 11 Example concert setup for percussion solo concert in Hindustani music.#

Raga grammar and performance#

Hindustani music is quintessentially an improvisatory music form in which the line between ‘fixed’ and ‘free’ is extremely subtle. In a raga performance, the melody is loosely constrained by the chosen composition but otherwise improvised in accordance with the raga grammar. In a typical Hindustani music concert, an artist executes variations of the raga characteristic phrases that represent the raga identity during the process related to improvisation. The characteristic phrases of a raga (pakad) are typically referred to in terms of notation but are fully described via the surface acoustic realization. The artist or performer uses his knowledge of the raga grammar to interpret the notation when it appears in a written composition in the specified raga. In this tradition like Carnatic music as well, compositions are handed down orally through the teaching lineage, and as a result, different lineages (gharana) may perform slightly different versions of the same composition.

Structure of a khayal performance#

There is a prescribed way in which a khayal performance develops. The least mixed variety of khayal is that where an alap is sung, followed by a full sthayi (first stanza of the composition) in madhya (medium) or drut (fast) laya (tempo), then layakari (rhythmic improvisation) and finally tan (fast vocal improvisation). When the elaboration reaches the higher (octave) Sa, the antara (second stanza of the composition) is sung. If the composition is not preceded by an alap, the full development of the raga is done through barhat. The composition is based on the general lines of the raga, the development of the raga is again based on the model of the composition.

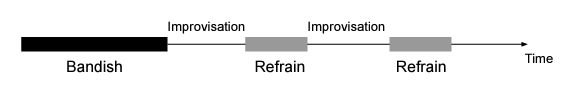

Fig. 12 Graphic showing the typical structure of a composition, e.g., a khayal. Time runs from left to right, with the bandish (composition) opening the sequence.#

In performance, a raga is typically presented in the form of a known composition (bandish) set in any appropriate metrical cycle (tala) within which framework a significant extent of elaboration or improvisation takes place. The performer is free to choose the tonic that is played on the drone in the background throughout the concert. A concert begins with slow elaboration of the chosen raga’s characteristics in an unmetered section called the alap. This is followed by the vistar which comprises the chosen composition and elements of improvisation. The progress of the concert is marked by the gradual increase of tempo with the duration of the rhythmic cycles decreasing and slightly more fast paced and ornamented rendering of the melodic phrases. While the raga grammar specifies a characteristic melodic phrase by a sequence of svara, the pattern serves only as a mnemonic to the trained musician to recall the associated continuous melodic shape or motif.

Improvisation in Indian music can be understood in terms of a small number of fundamental processes of development. These include the five, of which 2 relevant to our work on raga-specific phrase variations are: (i) rhythmic intensification: gradual increase in tempo melodic motif is reduced in length in successive repetitions; (ii) development of individual pitches: with a single pitch treated as the focus of attention for a while (“subject of discussion”). The music cues to this are the introduction of the note (has not yet appeared) in the gradually widening melodic range that slowly includes successively higher and/or lower pitches and the perceived emphasis.

A raga is brought out through certain phrases that are linked to each other and in which the svaras have their proper relative duration. This does not mean that the duration, the recurrence, and the order of svaras are fixed in a raga; they are fixed only within a context. The svaras form a scale, which may be different in ascending (arohana) and descending (avrohana) phrases, while every svara has a limited possibility of duration depending on the phrase in which it occurs. Furthermore, the local order in which the svaras are used is rather fixed. The totality of these musical characteristics can best be laid down in a set of phrases which is a gestalt that is immediately recognizable to the expert. In a raga some phrases are obligatory while others are optional. The former constitutes the core of the raga whereas the latter are elaborations or improvised versions. Specific ornamentation can add to the distinctive quality of the raga.

Raga epistemology#

The melodic form in Hindustani music is governed by the system of ragas. A raga can be viewed as falling somewhere between a scale and a tune in terms of its defining grammar which specifies the tonal material, tonal hierarchy, and characteristic melodic phrases. The rules, which constitute prototypical stock knowledge also used in pedagogy, are said to contribute to the specific aesthetic personality of the raga. In the improvisational tradition, performance practice is marked by flexibility and creativity that coexist with the strict adherence to the rules of the chosen raga. The empirical analyses of raga performances by eminent artists can lead to insights on how these apparently divergent requirements are met in practice.

Similarily to Carnatic Music, in practice most svaras in an Hindustani music performance are performed with alankar (ornamentation), rather than as plain notes. Technically a raga is a musical entity in which the intonation of svaras, as well as their relative duration and order, is defined. From the phrase outline we may filter certain svaras which can be used as rest, sonant or predominant; yet the individual function and importance of the svaras should not be stressed.

A nyas svara is defined as the resting svara, also referred to as ‘pleasant pause’ or ‘landmark’ in a melody. Vadi and samvadi are best understood in relation with melodic elaboration or vistar (barhat). Over the course of a barhat, artists make a particular svara ‘shine’ or ‘sound’. There is often a corresponding svara which sustains the main svara and has a perfect fifth relation with it. The subtle inner quality of a raga certainly lies in the duration of each svara in the context of the phraseology of the raga. A vadi, therefore, is a tone that comes to shine, i.e., it becomes attractive, conspicuous, and bright. Another tone in the same raga may become outstanding that provides an answer to the former tone. This second tone is the samvadi and should have a fifth relationship with the first tone. This relationship is of great importance.

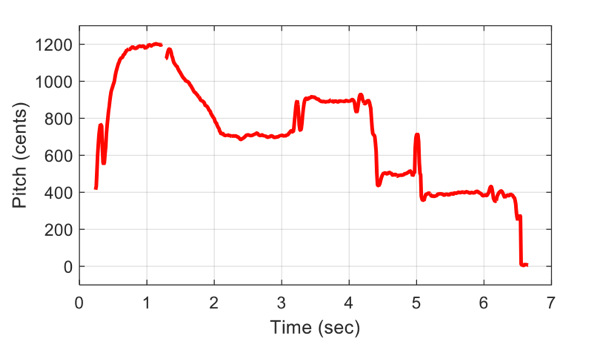

Fig. 13 Sample melodic contour from a phrase taken from raga Tilak Kamod performance by Ashwini Bhide, normalized with respect to the concert tonic. The svara transcription (note sequence) would be SPDmGS. The nyas vara, meend, and kan svaras are visible from the pitch contour.#

There are a few ways musicologists proposed melody transcription based on the alankars.

G P D ~, P D S \P, D \G – ‘\’ indicates glide (meend), ‘~’ indicates a nyas svara

D P P G G R S – superscripts are indicative of kan svara

D (P)G P, D P G (R)S – commas (‘,’) are resting points that delimit phrases and braces denote less emphasis or short duration of the svaras

Raga similarity: Allied ragas#

The notion of “allied ragas” is helpful in delineating the concepts for two “close” ragas. These are ragas with identical scales but differing in attributes such as the tonal hierarchy and characteristic phrases, because of which they may be associated with different aesthetics. Learners are typically introduced to the two ragas together and warned against confusing them. Thus, a deviation from grammaticality can be induced by any attribute of a raga performance appearing suggestive of an allied, or more generally, different raga. The overall perception of the allied raga itself is conveyed, of course, only when all attributes are rendered according to its own grammar.

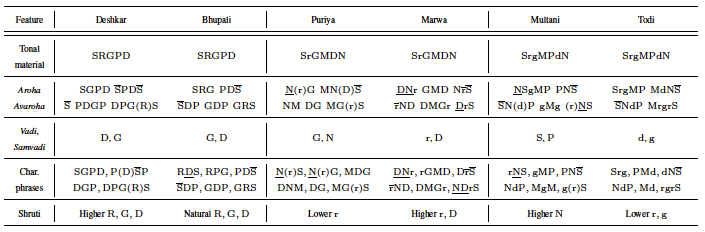

Fig. 14 Specification of raga grammar for three allied raga-pairs. Gaps in Aroha-Avaroha indicate temporal breaks (held svara or pause), under/overline are lower/higher octave markers.#

Canonical phrase shape: Motifs#

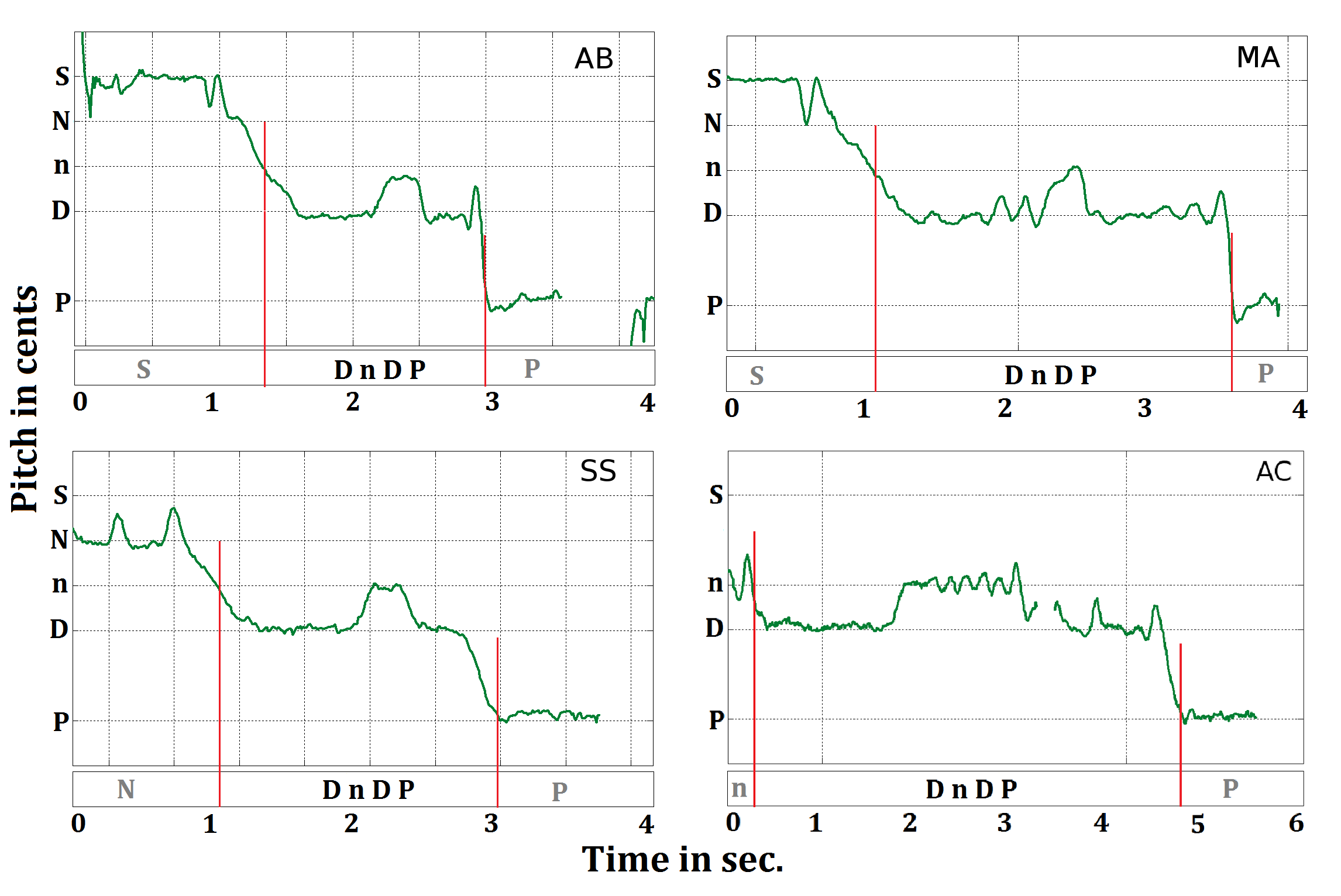

Notably, the key-phrases of a raga do not consist of any ornamentation but unmistakably consist only of notes. A motif is a sequence of svaras whose melodic realization includes specific intonations and transitions to/from neighboring svaras. In a typical Hindustani music concert, an artiste executes improvisations of the raga characteristic phrases that represent the raga identity. The characteristic phrases of a raga (pakad) are typically referred to in terms of notation but are fully described via acoustic realization. The artist or performer uses his knowledge of the raga grammar to interpret the notation when it appears in a written composition in the specified raga. The shape of a recurring melodic motif, in terms of continuous pitch vs. time, within and across performances of the raga shows variability in terms of one or more of the following aspects: pitch interval, relative note duration and shape of alankars (ornaments), if any, within the phrase, as seen in Fig. 15. The rules of the raga grammar are manifested at different time scales, at different levels of abstraction, and demand different degrees of conformity.

Fig. 15 Phrase shape of the DnDP phrase in raga Alhaiya Bilawal, exception is the bottom right phrase DnDP in raga Kafi. The difference in the canonical shape and the duration of ‘n’ is evident.#

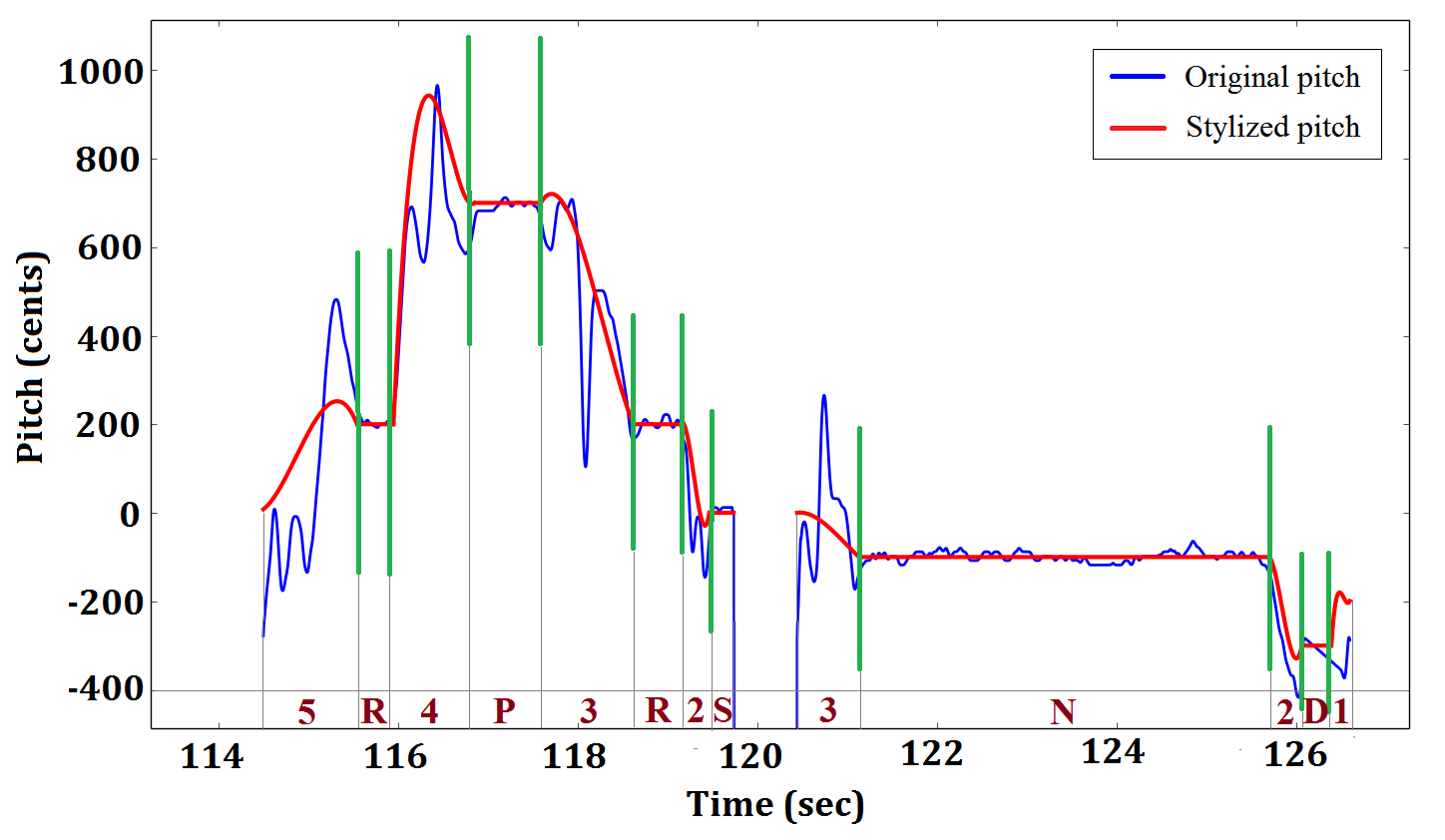

Fig. 16 Reconstruction of stylized contour from stable svaras and transients. The test phrase in the plot is from a concert in raga Sudh Sarang by Ajoy Chakrabarty.#

From Fig. 16, we observe that pitch oscillations are neglected and a lowpass trend is obtained as a stylized transient segment. This phenomenon is favorable for retrieval applications, because the oscillations (gamak) is not an essential, but occasional, part of a melodic phrase. Musicians choose to either apply or omit a gamak on based on local context. Hence, we are at a better chance of retrieving a phrase independent of the presence of gamak.

Long-term tonal hierarchy: pitch (class) distributions#

Raga performance allows for considerable flexibility in interpretation of the raga grammar in order to incorporate elements of creativity via improvisation. It is therefore of much interest in pedagogy to understand what ungrammaticality might mean in the context of a given raga, and possibly develop means to detect this in an audio recording of the raga performance. One prominent notion is that ungrammaticality is considered to occur only when the performer “treads” on another, possibly allied, raga in a listener’s perception. With this view, we aim to understand the technical boundary of a raga as that which separates it from another raga that is closest to it in its distinctive features. Even though it may be a bit unintuitive to imagine artists keeping track of the evolving tonal hierarchy (or key profile) maintaining the relative salience of svaras as performance develops. However, strikingly this is the case, and the tonal hierarchy captured via pitch (class) distributions has proven to be one of the successful features to classify ragas and also discriminate between allied raga-pairs.

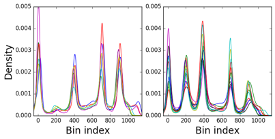

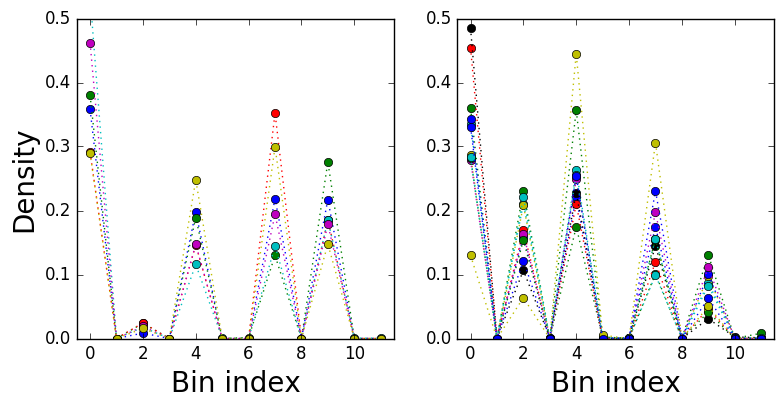

Fig. 17 Pitch salience histograms (octave folded, 1 cent bin resolution).#

Fig. 18 Svara salience histogram (salience is the cumulative duration of transcribed svaras) of 6 concerts in raga Deshkar (left) and and 11 concerts in raga Bhupali (right)#

Fig. 17 and Fig. 18 show the relative low salience of the ‘R’ svara in raga Deshkar with respect to raga Bhupali. This reconfirms the lexical information being manifested in performance captured via audio analyses. The tonal hierarchy can be estimated from the detected melody line of a performance. In Western music, pitch-class profiles extracted from music pieces, both written scores and audio, have served well in validating the link between theoretical key profiles and their practical realization. In the pitch-continuous tradition of Indian art music where melodic shapes in terms of the connecting ornaments are at least as important in characterizing a raga as the notes of the scale, it becomes relevant to consider the dimensionality of the first order pitch distribution used to represent distributional information. Music theory however is not precise enough to help resolve the choices of bin width and distance measure between pitch distributions. We use a novel musicological viewpoint, namely a well-accepted notion of grammaticality in performance, to obtain the parameters of the computational representation based on audio performance data, we maximized the discrimination of allied raga performances using well-known evaluation metrics. Pitch salience histograms, as well as the stable segment based svara salience and count histograms, were considered as distinct representations of tonal hierarchy. We considered a variety of distance measures in order to derive a combination of histogram parameters and distance metrics that best separated same-raga pairs from allied-raga pairs.

Note

Th sections above have been adapted, with consent, from the PhD thesis of Dr. Kaustuv Kanti Ganguli, at Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, India [Gan19].

Rhythm and Percussion in Hindustani Music#

As previously mentioned, several different styles of Hindustani music exist, each with it’s own variation of instrumentation. For example, the percussive accompaniment in a typical khyāl performance is the tabla, in the dhrupad style, it is the pakhāvaj. Here we focus on khyāl, the most popular style.

The artists in Hindustani music belong to what are called gharānās, or stylistic schools. Though all the gharānā use the same music concepts and basic style, each of them have their own nuances that are well distinguished and documented [Meh08].

Meter#

[Cla08] provides a comprehensive introduction to rhythm in Hindustani music. The definition of tāl in Hindustani music is similar to the tāḷa in Carnatic music. A tāl has fixed-length cycles, each of which is called an āvart. An āvart is divided into isochronous basic time units called mātrā. The mātrās of a tāl are grouped into sections, sometimes with unequal time-spans, called the vibhāgs. Vibhāgs are indicated through the hand gestures of a thālī (clap) and a khālī (wave). The first mātrā of an āvart (the downbeat) is referred to as sam, marking the end of the previous cycle and the beginning of the next cycle. The first mātrā of the cycle (sam) is highly significant structurally, with many important melodic and rhythmic events happening at the sam. The sam also frequently marks the coming together of the rhythmic streams of soloist and accompanist, and the resolution point for rhythmic tension [Cla08].

Tāl |

# Vibhāg |

# Mātrās |

Mātrā grouping |

|---|---|---|---|

Tīntāl |

4 |

16 |

4,4,4,4 |

Ēktāl |

6 |

12 |

2,2,2,2,2,2 |

Jhaptāl |

4 |

10 |

2,3,2,3 |

Rūpak tāl |

3 |

7 |

3,2,2 |

There are also tempo classes called lay in Hindustani music which can vary between ati-vilaṁbit (very slow), vilaṁbit (slow), madhya (medium), dr̥t (fast) to ati-dhr̥t (very fast). Depending on the lay, the mātrā may be further subdivided into shorter time-span pulsations, indicated through additional filler strokes of the tabla. However, since these pulses are not well defined in music theory, we consider mātrā to be lowest level pulse in the scope of this work.

As with Carnatic music, in Hindustani music there are significant differences in terminology describing meter when compared with Eurogenetic music. The definition of beat pulsation, as foot tapping instances in time, is also a problem with Hindustani music. Depending on the lay, the mātrā can be defined to be the subdivisions (for dr̥t lay) or as beats (for vilaṁbit and madhya lay). To maintain consistency, using accepted conventions, we note that the concepts of mātrā and the āvart of Hindustani music bear analogy to the beat and the bar metrical levels of Eurogenetic music. This implies that there is no well defined subdivision pulsation defined in Hindustani music. The possibly unequal vibhāgs are the sections of the tāl.

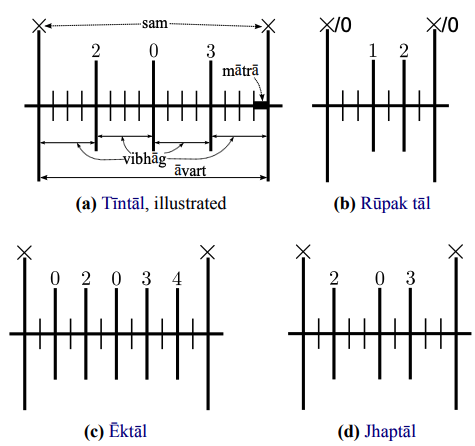

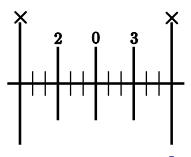

There are over 70 different Hindustani tāls defined, while about 15 tāls are performed in practice. Fig. 19 shows four popular Hindustani tāls - tīntāl, ēktāl, jhaptāl, and rūpak tāl. The structure of these tāls are also described in Table 3. The figure also shows the sam (shown as ×) and the vibhāgs (indicated with thālī/khālī pattern using numerals). A khālī is shown with a 0, while the thālī are shown with non-zero numerals. The thālī and khālī pattern of a tāl decides the accents of the tāl. The sam has the strongest accent (with certain exceptions, such as rūpak tāl) followed by the thālī instants. The khālī instants have the least accent.

Fig. 19 An āvart of four popular Hindustani tāls, showing the mātrās (all time ticks), vibhāgs(long and bold time ticks) and the sam (×). Tīntāl is also illustrated using the terminology used in this article.#

Fig. 20 An alternative structure of Ēktāl in dr̥t lay#

A jhaptāl āvart has 10 mātrās with four unequal vibhāgs (Fig. 19d), while a tīntāl āvart has 16 mātrās with four equal vibhāgs (Fig. 19a). We can also note from Fig. 19b that the sam is a khāli in rūpak tāl, which has 7 mātrās with three unequal vibhāgs.

The special case of ēktāl needs additional mention here. Ēktāl has six equal duration vibhāgs and 12 mātrās in a cycle as shown in Fig. 19c. However, in dr̥t lay, an alternative structure emerges, which is represented as four equal duration vibhāgs of three mātrās each as shown in Fig. 20. For consistency, we use the structure as shown in Fig. 19 here.

Percussion in Performance#

Hindustani music uses the tabla as the main percussion accompaniment. It consists of two drums: a left hand bass drum called the bāyān or diggā and a right hand drum called the dāyān that can produce a variety of pitched sounds.

Tabla acts as the timekeeper during the performance indicating the progression through the tāl cycles using pre-defined rhythmic patterns (called the ṭhēkā) for each tāl. The lead musician improvises over these cycles, with limited rhythmic improvisation during the main piece. The ṭhēkās are specific canonical tabla bōl patterns defined for each tāl as illustrated in Fig. 21. However, the musician playing tabla improvises these patterns playing many variations with filler strokes and short improvisatory patterns. [Mir11], [Cla08], [Dut95], [Ber08], and [Nai05] provide a more detailed discussion of tāl in Hindustani music including ṭhēkās for commonly used tāls.

Fig. 21 The ṭhēkās for four popular Hindustani tāls, showing the bōl for each mātrā. The sam is shown with × and vibhāgs boundaries are separated with a vertical line. Each mātrā of a cycle has equal duration.#

To showcase the nuances of a tāl as well as the skill of the percussionist with the tabla, Hindustani music performances feature tabla solos. A tabla solo is intricate and elaborate, with a variety of pre-composed forms used for developing further elaborations. There are specific principles that govern these elaborations [Got93]. Musical forms of tabla such as the ṭhēkā, kāyadā, palaṭā, rēlā, pēśkār and gaṭ are a part of the solo performance and have different functional and aesthetic roles in a solo performance. A percussion solo shows a variety of improvisation possible in the framework of the tāl, with the role of timekeeping taken up by the lead musician during the solo.

In Hindustani music, the tempo is measured in mātrās per minute (MPM). The music has a wide range of tempo, divided into tempo classes called lay as described before. The mainly performed ones are the the slow (vilaṁbit), medium (madhya), and fast (dr̥t) classes. The boundary between these tempo classes is not well defined with possible overlaps. In this dissertation, after consultation with a professional Hindustani musician, we use the commonly agreed tempo ranges for these classes: vilaṁbit lay for a median tempo between 10-60 MPM, madhya lay for 60-150 MPM, and dr̥t lay for >150 MPM. This large range of allowed tempi means that the duration of a tāl cycle in Hindustani music ranges from less than 2 seconds to over a minute. A mātrā in vilaṁbit lay hence can last about 6 seconds, and to maintain a continuous rhythmic pulse, several filler strokes are played on the tabla. Hence the surface rhythm apparent from audio recordings can be quite different from the underlying metrical structure.

Bōls#

Similar to mridangam, the tabla repertoire is transmitted using onomatopoeic oral mnemonic syllables called the bōl. Tabla has different stylistic schools called gharānās. The repertoires of major gharānās of tabla differ in aspects such as the use of specific bōls, the dynamics of strokes, ornamentation and rhythmical phrases [Ber08]. But there are also many similarities due to the fact that the same forms and standard phrases reappear across these repertoires [Got93].

The bōls of the tabla vary marginally within and across gharānās, and several bōls can represent the same stroke on the tabla. To address this issue, we grouped the full set of 38 syllables into timbrally similar groups resulting into a reduced set of 18 syllable groups as shown in Table 4. Though each syllable on its own has a functional role, this timbral grouping is presumed to be sufficient for discovery of percussion patterns. For this work, we limit ourselves to the reduced set of syllable groups and use them to represent patterns. For convenience, when it is clear from the context, we call the syllable groups as just syllables and denote them by the symbols in Table 4. A brief description of the timbre is also provided for each syllable.

Bōls |

Symbol |

Description |

|---|---|---|

D, DA, DAA |

DA |

A closed stroke on the dāyān (right drum) |

N, NA, TAA |

NA |

A ringing stroke on the dāyān |

DI, DIN, DING |

DIN |

An open stroke on the dāyān |

KA, KAT, KE, KI, KII |

KI |

A closed stroke on the bāyān (left drum) |

GA, GHE, GE, GHI, GI |

GE |

A modulated stroke on the left drum |

KDA, KRA, KRI, KRU |

KDA |

Two quick successive strokes (played as a flam), one each on dāyān and bāyān |

TA, TI, RA |

TA |

A closed stroke on the dāyān |

CHAP, TIT |

TIT |

A closed stroke on the dāyān |

DHA |

DHA |

A resonant combined stroke with NA and GE |

DHE |

DHE |

A closed combined stroke played with the full palm on the dāyān with a closed GE |

DHET |

DHET |

A combined stroke played with a closed stroke on dāyān with GE |

DHI |

DHI |

A closed combined stroke with GE and a soft resonant stroke on dāyān |

DHIN |

DHIN |

An open combined stroke with GE and a soft resonant stroke on dāyān |

RE |

RE |

A closed stroke on the dāyān played with the palm |

TE |

TE |

A closed stroke on the dāyān played with the palm |

TII |

TII |

A combined stroke with KI and a soft closed resonant stroke on dāyān |

TIN |

TIN |

A combined stroke with KI and a soft open resonant stroke on dāyān |

TRA |

TRA |

Two quick successive closed strokes on dāyān (played as a flam) |

Note

The section above has been adapted, with consent, from the PhD thesis of Ajay Srinivasamurthy [S+17]